This story, originally published on June 27, 2015 for another blog, is a departure from the portrait posts I make here on my photography web site. Frankly, I wanted to preserve the account, and since this is my own web site, I figured, what the heck! Just put it here. Please…enjoy!

In 1939, the United States military ranked 18th in the world and the US Army Air Corps had about 1700 aircraft, all fighters and trainers. (1)

Between 1940 and 1945, the United States produced $183 billion in arms. Shipyards on the east and west coasts launched 141 aircraft carriers, eight battleships, 807 cruisers, destroyers and destroyer escorts and 203 submarines. Factories built over 88,000 tanks and self-propelled guns, 257,000 artillery pieces, 2.4 million trucks, 2.6 million machine guns and 41 billion rounds of ammunition. (2)

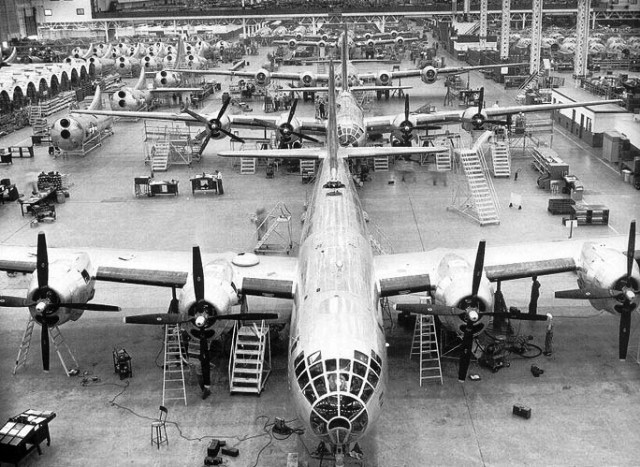

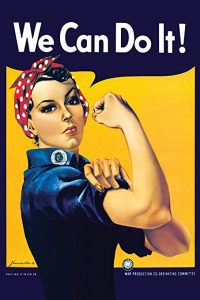

By 1942, American workers, mostly women, were turning out 170 aircraft a day, totaling 324,750 by the end of the War. In all, 3970 Boeing B-29 “Superfortress” aircraft were built. The B-29 was built to deliver victory. As victory in Europe was achieved, General MacArthur detailed “Operation Downfall”, a planned invasion of Japan that estimated one million US casualties.

President Truman made a decision that changed the world forever. On August 6 and August 9, 1945, two Boeing B-29 “Superfortress” bombers dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. No other aircraft in the world could deliver the payload. Only the B-29 was capable of carrying those weapons that ended WWII. As horrific as that was, the war was over.

Japan surrendered. As servicemen returned home, aircraft were retired to the desert southwest, including China Lake in the Mojave desert and Arizona. B-29A serial number 44-62070 was officially retired in 1958. (3) It was sent to China Lake, California and put into storage.

In 1971, the Commemorative Air Force (then known as the Confederate Air Force) was looking to add a B-29 to it’s collection. The CAF found B-29A, s/n 44-62070, “FIFI”. After nine weeks of work at China Lake, often taking parts from other B-29s, FIFI was flown to the CAF headquarters in Texas.

The Commemorative Air Force’s mission is to preserve and restore aircraft in flying condition as well as to perpetuate the memory of the aircraft that have been flown in defense of our nation. In the pursuit of their goals, the CAF tours around the country, bringing a portion of its collection of aircraft to cities so people can tour them, even ride in them. Rides are not cheap, but the revenue supports the CAF’s mission.

I had been watching the CAF tour schedule because of Kim Pardon, who I got to know as a moderator and participant in an aviation web forum. She is a CAF member. It was my goal to see FIFI when the tour came to Rochester, NY in June 2015 and meet Ms. Pardon in person.

Well, that weekend came and while many of my friends from the Williamson Flying Club managed to see FIFI at the Rochester Airport, I was unable to get there for a tour. I resolved to watch the CAF tour schedule and wait. FIFI’s next stop was Nashua, New Hampshire. Likely I would not get a chance to see FIFI, or meet Kim for probably another year.

Life was not to be so unkind.

Late Wednesday, I heard the familiar p-ting! of my phone alerting me to a text message. It was from Kim, “We are transitioning FIFI from Rochester to Nashua on Friday. We have an empty seat. Would you like to ride along?”

There are few times in life when one gets an offer one cannot refuse! Clearly, the offer to ride in FIFI was one of those times.

I showed my wife the text message. She simply said, “Of course you would!”

At nine in the morning on Friday, I walked into the FBO where FIFI was parked. Like many days when a VFR flight is planned, the sky was overcast with a thin cloud layer at 1100 feet above the ground. It was also cooler than forecast, which meant that the clouds were not going to rise very soon to a level that would allow for a safe cross-country flight of 300 miles. As eleven AM approached, the clouds were getting higher. The forecast was looking good for a one o’clock departure.

Someone said, “We’re hungry. Let’s eat.” I learned that the crew, which had been in Rochester for over a week, had eaten most every meal at Jay’s Diner, a landmark that was popular even when I was in college. Given that I hadn’t eaten there in over 30 years, I thought it would be nostalgic to order the BLT, a favorite of mine back then. It was delicious. On our ride back to the airport shortly after noon, it was clear that the clouds were about 1000 feet higher than they were at nine. It was also much warmer. Through the thin layer, I could see patches of blue, teasing, yet promising that the skies were clearing. The crew agreed that one o’clock was “go time”.

We all took care of our creature needs and then walked across the tarmac, where FIFI stood as ready for flight as she did in 1944. The sun glinted off her silver skin, made steel gray by the thin overcast. The nacelles around her mighty engines showed streaks of oil and exhaust that betrayed FIFI’s need for constant care and maintenance.

A B-29 crew includes a pilot and copilot, a flight engineer, bombardier, radio operator, navigator, port waist-gunner, starboard waist-gunner, top-gunner, radar operator and tail gunner. We agreed that I would sit in the bombardier’s seat at departure. That’s the seat in the nose of the plane, facing the world through windows of plexiglass fitted into a web of aluminum ribs. Part way through the flight, I would switch with Andy, the other rider and fellow friend of Kim’s, who would sit in the bombardier’s seat upon landing at Nashua, his home airport.

As I ducked under the nose wheel doors to climb the ladder into the plane, I marveled at my first glimpse inside FIFI. Both shiny and aged, hulky and streamlined, she captured an amazing moment in time when aviation met technology that was the very best American industry could produce, more importantly, mass produce. I climbed carefully, noting the position of hand-holds and taking care to avoid touching any levers or switches, or bumping my head anywhere, as I made my way to my assigned departure seat, the bombardier’s position.

Once everyone was aboard, Phil raised the ladder and assigned it to its in-flight position just fore of a tube through which one could crawl to get to the waist and tail-gunner positions.

The B-29 was the first pressurized warbird and thus could fly higher than enemy fighters, making it mostly invulnerable to enemy fire. Rather than depressurize to drop a bomb load, the tube was the solution to allow the crew compartments, fore and aft, to be connected and remain pressurized when the bomb bay doors opened. Manufacturing ingenuity meets wartime requirement.

The process of starting the engines took what seemed to be the better part of an hour, but was more likely 30 minutes. It began with calling Rochester airport’s fire department to ask for a fire truck to be present. Standard procedure, I learned. Before long, three of Rochester Airport’s fire trucks were in attendance. One can only imagine that watching the world’s only flying B-29 was a pleasant diversion to the drudgery of waiting for an emergency to be declared so you can roll the equipment.

As each of the four massive engines started, reluctantly, after a dozen or so revolutions of each propeller, FIFI shuddered and then was alive. The heartbeat of her engines gave the entire aircraft purpose. Feeling FIFI alive as her long-since-gone crew felt her was a gift, thanks to the volunteers of CAF.

With all four 2000 horsepower engines roaring, we began our taxi to runway two eight. The B-29 has a free-castering nose wheel, much like the front wheels on every shopping cart. Steering on the ground is accomplished by applying brakes to the main gear. Tap the right brake to go right, left brake to go left. I could feel a tap here and there as the pilot negotiated the taxi from the tarmac via taxiways Kilo, Foxtrot and Papa.

We lined up short of the RW 28 ILS Hold Short line. As the engines were run up, one at a time, FIFI shook and vibrated and bounced. Once run-ups were completed, we taxied out to the departure end of RW 28. The engines went to full throttle. Fifi bounced and swayed, eager to roll. After a moment, I felt the brakes release, and we were moving. I was about to get the ride of my life!

As the runway markings slid beneath us at an increasing speed, FIFI hitched left or right to stay roughly on center line as the pilot tapped the brakes to control direction. The rudder on a B-29, as big as it is, is not effective until the aircraft hits 60 or 70 mph. We hit that speed and corrections became smoother, more aerodynamic. Then we were airborne.

The B-29’s departure is not designed to gain altitude, but to gain airspeed. With airspeed comes engine cooling. With airspeed, eventually, comes altitude. We rose slowly over the railroad and the neighborhoods in Gates then turned east toward our destination in New Hampshire. (There is a link to a video of the takeoff at the bottom of this article.)

We stayed below the overcast, which was roughly 3000′ AGL, which put our initial cruise altitude at about 3000 MSL. As we flew east, the cloud layer remained solid but thin. While cruising, I looked over at the bomb sight to my right and noticed that it was manufactured by the General Railroad Signal Company, of Rochester, NY. I wondered how many other parts and systems on the aircraft were manufactured by Rochester companies like Kodak, Bausch & Lomb, and Rochester Gauges.

I turned back from my seat and watched the pilot and copilot, two of the luckiest souls on the planet. The pilot sported a handlebar mustache and a constant smile. After a military career, he joined the CAF so he could help share the history of America’s warbirds. Every ten minutes or so, the pilot would turn over the controls to the copilot, a man of calm demeanor and an intensity of purpose.

Somewhere between Palmyra and Syracuse, a decision was made to climb above the clouds and continue to Nashua. And we did. From my position, I contemplated the role of the bombardier. Identify target, calculate, bomb. Pretty straightforward, just like the “Bombardier’s Checklist” hanging just to my left. It had only three items, “Look Down”, “Aim at Japan”, “Remember Pearl Harbor”.

Honestly, I have to say the rest of the flight, I just soaked in the sounds, smells, vibrations and details of the airplane. At the halfway point, I switched seating positions with Andy, who took the bombardier’s seat as we prepared to land at his home airport in Nashua, NH.

I took this opportunity to photograph the Engineer and his apprentice, as well as many details of the aircraft.

The Flight Engineer is a singularly focused gentleman who sits aft of the copilot, facing aft. His responsibility is to apply proper power settings to the four engines, each with 18 cylinders, for every phase of flight, from taxi to cruise to shut-down.

The flight engineer never wavered from his duties of giving the pilot the power settings needed to depart, climb, cruise, descend, land and taxi to the parking spot in Nashua.

After what I thought was a perfect landing at Nashua, I heard the pilots talk about what they did wrong, and how they can fix those things so they never do them again. It was a learning experience, but mostly a humbling experience. Even as volunteers, the crew held to the strictest of high standards for performance, communication and expectations.

Most of the men who fought in WWII are gone. Those few that still are with us are in their 90’s. Most of the women that built the tanks, boats, airplanes and arms are gone. But the impact these men and women had on America will live on, if we choose to remember it.

The Commemorative Air Force’s mission “to perpetuate the memory of the aircraft that have been flown in defense of our nation” is met by the spring, summer and fall schedule of the CAF and their dedication to bringing these aircraft to the people.

Tours of aircraft in museums are nice, exposure to war birds on the ground while behind rope lines are good, but museums are graveyards with artifacts. Rope lines around silent aircraft guide viewers past an object that cannot be fully understood because the power is not evident. It’s just an object on display. If the Commemorative Air Force’s mission is to “perpetuate the memory of the aircraft that have been flown in defense of our nation” then I learned that memory is best perpetuated by being in an aircraft that is alive and aching for the sky.

The energy and passion that the crews of FIFI and all the other aircraft that the squadrons of CAF crews who donate their time and talent so we all remember is a national treasure.

My ride along in FIFI is one flight I will never forget.

All photos, unless otherwise credited, are (c) 2015 by the Author.

1 – American National Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999) Vol. 12, 84

2 – Freedom’s Forge (New York, Random House, 2013) Arthur Herman3

3 – Chinnery 1985, p. 195.